Mogg Morgan (c)

The literary vocabulary is peppered with metaphors of food and eating. We talk of good taste, to savour something or of food for thought. In this article I hope to show that this use of language is not accidental and in fact leads us to the heart of poetry. The contention that the mental feelings of enjoyment are indebted to bodily or physiological feelings may be difficult for some people to accept. We are inclined to draw a strict dividing line between mind and body; but this has not always been so, nor need it be in the future.

Aristotle in his Poetics speaks of “Catharsis” which is also a medical term meaning cleansing or purging a crucial component of the medical practice of his time (Poetics 1448b4-17). Aristotle was a physician as well as a philosopher and in the system of healing he practiced, which was based upon the Humours, Catharsis would have brought the sick person back to a state of psycho-somatic equipoise or isonomia

The similarities between Greek ideas and those of ancient Indian aesthetics are so striking that it is highly probably that they derive from a common source, which could be Egypt.

The oldest system of Indian medicine is called Ayurvedic, which is a compound of two words, “ayur” meaning longevity and “veda” meaning knowledge. The main textual sources of Ayurveda go back to about the beginning of the present era. Many of its ideas are much older and derive from a very creative period in Indian culture at around the sixth century BCE (ie not thousands of years BCE but a time of intellectual and spiritual rebirth). Ayurveda views the world rather like a vast organism, in which all the parts are interconnected. The essence of this organism is a constantly changing liquid called “rasa”, and so one analyses all its various parts by the sense of taste, which in sanskrit is the same word “rasa”. This homonym has a number of interesting and related meanings, including Sap, liquid, essence, elixir, serum, chyle, mercury, semen, taste, feeling, and sentiment. Therefore the sense of taste is the connecting link between an individual and the larger whole; an idea that has very wide implications in art and culture. In this system there are said to be six varieties of taste: sweet, Sour, Saline, Pungent, Bitter and Astringent.

According to the Ayurvedic system what one eats, and therefore tastes is also the cause both of health and illness.(1) This is because all foods are broken down in the stomach into a pure liquid food chyle, (rasa) and its waste products. In this process three humours are also produced, in Sanskrit they are called Vata, Pitta and Kapha, and they are sometimes translated as Wind, Bile and Phlegm. The term humour is a translation of the Sanskrit word “dosha” which means to spoil; although these substances are essential constituents of the human body, but if they are produced in too great a quantity or in the wrong part of the body they are the fundamental cause of all diseases that afflict humanity. Thus one form of Bile keeps the skin in a good tone, but if there is too much of it leads to swelling.

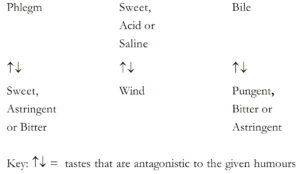

The Ayurvedic system tells us that there is a dynamic relationship between the three humours and the six tastes. For example:

Bile, which is oily, hot, sharp, liquid, sour, fluid and pungent is soon overcome by medicine having opposite qualities.

Wind, which is rough, cool light, subtle, mobile, non-slimy and coarse, is reconciled by medicines having opposite qualities.

Phlegm, which is heavy, cool, soft, oily, sweet, immobile and slimy is relieved by medicine of opposite quality.(2)

The relationship between tastes and humours is complex but can be represented in a very simplified form by the following diagram:

Equipoise is achieved by manipulation of these relationship through the food that one eats, so that a person is restored to or maintained in good health by an appropriate diet.

How all these factors effect the Mind gives us the link between medicine and art. The Indian intellectual tradition makes a division between Consciousness and the Body which is quite alien to that of the Western tradition. The Indian tradition divides all phenomena into two broad categories of spirit and matter. On one side is purusha, the transcendental aspect of ones personality, and on the other is ranged all our physical attributes, which in this system includes the Mind (manas), the Intellect (Buddhi) and the Senses (indriya). Thus ones mental sensitivities, although they are constructed from a finer material than the more gross aspects of the body, are still essentially part of the same model of causes and effects outlined above. The Mind has its food just like any other part of the body. Thus insanity (unmaada) means literally intoxication. Mental equipoise is achieved by reference to an allopathic model of mental tastes designed to counteract a particular temper.

The aim of Sanskrit poetry is to create a state of bliss in the hearer, an “impersonalized and ineffable aesthetic enjoyment from which every trace of its component ..material is obliterated.”(3) Aesthetic enjoyment is both a means of achieving perfect mental balance and ultimate salvation. This transcendental aspect of poetry is something lost in the present day, but would have been taken for granted by our ancestors. Plato spoke of the power of art to bring about spiritual liberation, and this tradition flows strong in the history of Celtic Bardic traditions. A good poem is often still recognized by the mysterious frisson it brings about.

Sanskrit poetry has several different moods designed to provoke particular emotions. “Mood” is another possible translation of the Sanskrit “rasa”, literally the taste or flavour of something. This is more than an accidental homonym. The fact that the same word occurs in medical and poetic texts has to mean that there is a fundamental unity of outlook.(4) There are eight or sometimes ten moods in Indian poetics: Love, Courage, Loathing. Anger, Mirth, Terror, Pity and Surprise and optionally tranquility and paternal fondness .

Interestingly Yeats used the term “Mood” in a short piece on the purpose of poetry published in Ideas Of Good & Evil, page ?? this volume.

Perhaps the most widely used Mood is the erotic one, as it is a remarkable feature of Indian culture that the spiritual truths are most often conveyed by erotic images. Thus the story of Krisna’s dance with the Cowherd’s wives conceals an essential spiritual message. Each girl dances with Krisna and feels that she is unique. This symbolizes the mystery of the communion of the multiplicity of all human souls with the undivided Absolute. This theme is the subject of one of Indian most treasured poems, Jayadeva’s Gitagovinda or “Love Song of the Dark Lord”. which should be sung with Raga Vasanta or Spring Mode

Soft sandal mountain winds caress quivering vines of clove.

Forest huts hum with droning bees and crying cuckoos

When spring’s mood is rich, Hari roams here

To dance with young women friend–

A cruel time for deserted lovers.(5)

Indian poetry is created within a totally integrated philosophy of the human psyche and body. Our aesthetic sense, literally our sense of taste, connects us to the wider universe of which we are only a small part. Perhaps here lies the mysterious secret of poetry. Its ability to lift us up out of ourselves, at the same time purifying and healing our alienated nature. The basis of which Indian poetical works may strike some as too literal an interpretation of the facts. However these ideas completely permeate the art of the sub-continent and have generated some of the most sublime artistic creations of any culture.

Mogg Morgan

1 Agnivesha’s Caraka Samhita translated in English by R K Sharma and Vaidya B Dash (Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office, Varanasi 1976) I.xxv.29

2 ibid I.i.59-61.

3 S K De History of Sanskrit Poetics (Calcutta 1960) page 37

4 R K Sen Aesthetic Enjoyment and Its Background in Philosophy and Medicine. (Calcutta 1966)

5 Jayadeva’s Gitagovinda – Love Song of the Dark Lord Edited and translated by Barbara Stoler Miller (Columbia University press 1977)